Supposed to have been stabbed to death in a duel in 1705 or thereabouts, we find ourselves disappointed by reality…

The Bleikeller (“lead cellar”) of St.Peter’s Cathedral in Bremen, Germany, contains the desiccated remains of 8 people from the 17th and 18th centuries. Comparatively well preserved (everything considering), the Bleikeller mummies have attracted thrill-seekers for a good three-hundred years.

The reputed former inhabitants of these mortal shells make for mixed company—in fact, they resemble the cast of a late-1970’s sit-com, complete with a Swedish countess, an English Lady, a coronet, a general, a pauper who donated his body to “science”, and a roofer who supposedly fell off the tower sometime in the late 1400’s.

All that’s missing is the Professor and Mary Anne. Not to mention Ginger Grant.

In his out-of-print book Bleikeller, oder der Dachdecker, der kein Dachdecker war (Bremen: Johann Heinrich Döll Verlag, 1985) Wilhelm Tacke injects a dose of reality into the earnest tall tales imparted by curators and guides over the centuries, thereby unraveling the chronological accumulation of reported junk fact. Suffice to say, the English Lady turns out not to have been English or a Lady at all, the Swedish countess was neither Swedish nor a countess—and the roofer didn’t die from a fall but, far more interesting than a workplace accident, from a bullet lodged in his spine.

One of the departed caught our eye, the Student who Died in a Duel, supposedly in 1705. After having spent unreasonable amounts of time searching for records (such as early newspapers) that would provide a solid lead, Tacke’s book provided the coup de grace.The first mention of the dead Studiosus comes by way of Pastor Poppe of Friedersorf, who (in a letter to the remarkably-titled Brunzlauische Monathschrift of 1779) reminisces about a visit to the Bleikeller said to have taken place in 1748. He writes that he had seen 5 mummies, one of them “a man of medium stature, dressed in a shirt. They say he was a student who was stabbed to death, without providing particulars. On the left side, his shirt looked very bloody.” Another tourist, Mylius, in 1753 mentions that the student had been stabbed “through his left arm”. It’s not until 1805 that custodian Hans Heinrich Wedemeyer supplements that this happened “in a duel.”

Late 19th-century narrative filler provides a pretty patrician heiress persecuted as a witch, a broken blade, and the entry of a puzzle to make all of this plausible, but a late 20th-century x-ray provided no indication of internal injury. However, there is indeed a visible defect to the lower left arm:

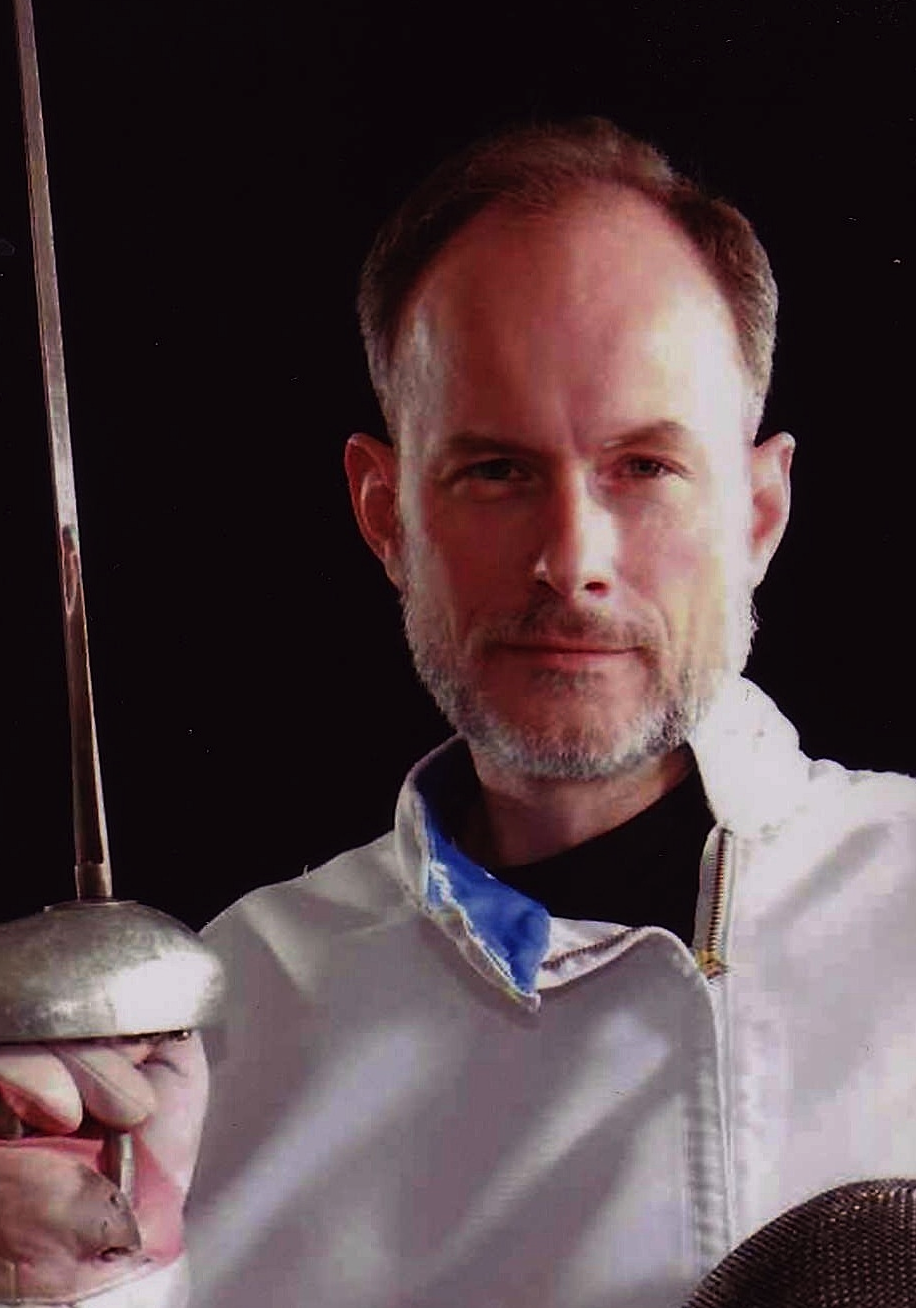

Of course, that “wound” bears no resemblance to the tell-tale, three-flanged incision caused by a smallsword. In fact, it looks like a hole made by a .45 or poker. Or, post-mortem, by the probing fingers of visitors who, throughout the 19th-century, were known for breaking off little bits of mummified tissue (whole fingers even) to take home as a souvenir. And unless the young man was a leftie, the outer surface of the left arm would not have been a prime target for a fencer trained in the French method, and a difficult, most likely random hit if received by a Kreusslerian.

Would it have been a potentially lethal wound? Hard to say. We tend to stick with the perennial wisdom of Dr. Theodore King, of Maryland’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, who—when testifying as an expert witness regarding the cause of death of homicide victims—routinely will answer the defense attorney’s question “Was that wound fatal?” with “All wounds are potentially fatal.”