Reduced weight.

Reduced weight.

Upside-down mounted blades.

A sneakily set handle.

Early attempts in gaining an unfair advantage with épées de combat.

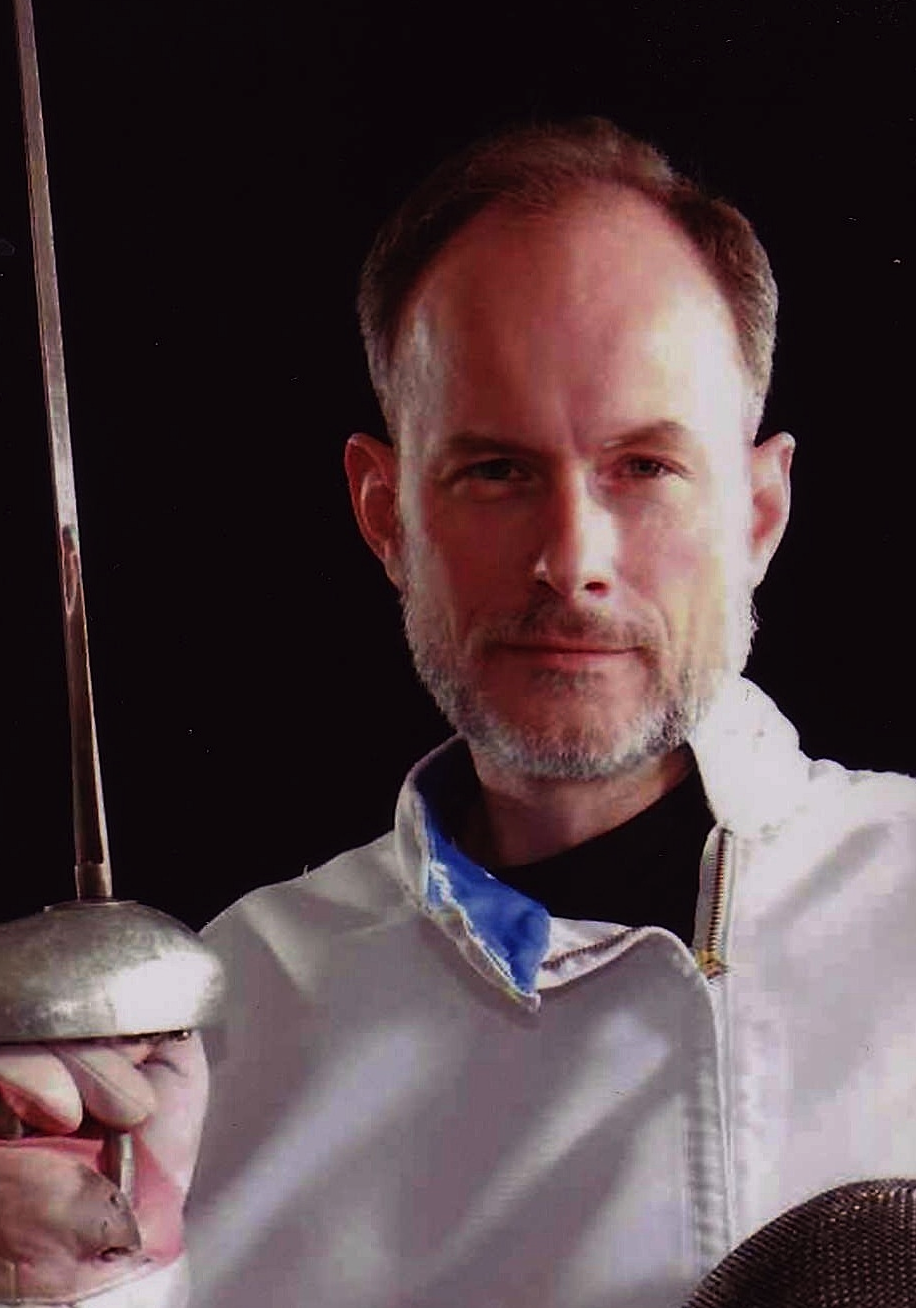

—by J. Christoph Amberger

Among the weapons that adorn every nook and cranny of the Amberger Collection’s lavish exhibition halls, there are about 40 19th-century dueling and early competition épées. Most are of French manufacture, and all feature the characteristic hollow-ground triangular blade. Some of the weapons have been sharpened to points of various acuteness. Most are “blanks” with rebated (i.e., flattened) points — they are not unlike the heads of common nails. These are equally suitable for being wrapped with string and leather for practice or for the application of a metal file prior to a duel. Later versions have points d’arrets or early attempts at spring-loaded tips.

The overall shape of these blades is familiar to every modern fencer: Modern variations, with screwed-on spring-loaded tips and a groove cut to accommodate the wire, still can be found in every modern fencing and competition épée.

While international standardization of weapon configuration has made modern weapons almost indistinguishable to the untrained eye, the hilts of early épées reflect the full palette of styles available for foils in the first and second thirds of the 19th century. (It’s not until the 1880’s that the familiar steel bell guard begins to dominate.)

There are bell guards of varying depth and diameter, flat circular plates, shallow discs with the concave side both mounting toward and away from the fencer, and elaborately adorned lobes and shells made of both brass and steel. (We‘ve covered some patterns here!)

But regardless of the varieties of guards, most weapons follow the standard pattern of mounting the blade, with the broad side up and the spine pointing down: When looking down at his blade, the fencer sees the broad base of the triangle near the guard. In the modern blades, it’s where the wire enters the hilt. In the older blades, it’s traditional real estate for the maker’s or fournisseur‘s mark.

The Upside Down Group

There is, however, a sub-group of mid-19th-ct. dueling weapons that, literally, turns this standard assembly in its head: Here, the blades are mounted with the narrow spine pointing up: The base of the triangle faces down, the apex up.

Above: Two matched pairs of 19th-ct French dueling épées, with the blades mounted upside down. (Type A 1 &2 on the left, Type B 1 & 2 on the right).

When I contacted several of my fellow collectors in Germany and Britain, asking if they could point me to sources in which this orientation of the blade would have been mentioned in the literature of épée fencing, the response was almost identical: While my colleagues had a few weapons with the same blade-mounting in their collections, they had ascribed this to an assembly error.

However, two matched pairs of weapons in my collections indicated that error may have been unlikely: Both pairs are high-quality, top-of-the-line weapons. The blades exhibit the characteristic bend of fencing (or dueling) blades familiar to modern fencers: The curve downward from the hilt to the point to allow the blade to bend in one direction only during a hit.

Only that here, the blades are bending that way with the spine on top and the flat down.

Type A, 1 & 2: Note the slight downward curve in the handle!

The hilts, too, support thought and intent behind this pattern. The weapons I am calling Type A for the sake of this article, have perfectly sculpted, slightly downward bending handles. A wide central groove in the center makes them extremely comfortable to hold—but only when the blade is held so its spine is pointing upward.

(Type A has another rare—albeit not altogether unheard-of—characteristic: The iron guard is mounted with the concave side toward the opponent, not toward the fencer.)

Type B, 1 & 2: Bronzed steel bell guards with upside-down blades.

If the Type A weapons indicate intent in the unconventional assembly of blade and hilt, the Type B weapons remove any doubt that the assembly was not only intentional and deliberate, but done with additional thought into giving an unfair advantage to one of the fencers:

While blades of equal length for purposes of dueling and fencing are mentioned in Shakespeare, the commonly carried sidearm of the 15th-through 18th centuries was a personal affair, reflecting considerations of more or less ostentatious wealth and fashion, status, and personal preference. Dueling weapons, however, had to be identical—or at least as close to identical as possible.

***

“If you can’t laugh with them, laugh at them!”

Amberger’s Alchemia Dimicandi: The Final Cut

***

Lacking binding standards, this meant that weapons intended for dueling had to be made and sold in pairs. (Indeed, even today, the fact that two identical historical épées or smallswords are still together and sold in a pair allows for the inference that dueling was at least a realistic ultimate use for them… even if the blade blanks never were honed down to the prerequisite points).

Type B: Some of the best thought-out handles I’ve seen!

Both Type A and Type B meet these criteria. In fact, except for a 50g difference in weight (possibly due to a slightly thicker or wider tang), Weapons 1 and 2 of Type A are virtually identical.

But take a gander at the numbers:

The Unfair Advantage

It is the subtle differences in Weapons 1 and 2 of Type B (see above table) that permits a plausible inference that error played no role in the mounting of the blade, but that, to the contrary, each element of the weapons was not only well thought-out—but deliberately designed to give one fencer (or duelist) a slight advantage.

It is these weapons were the “set” of the blades is most pronounced: The pommel of Weapon one, at the end of a 6 1/2″ long, sharkskin and wire-wrapped handle, deviates about an inch southward from the center of the opening. For a period where weapons mostly maintained a straight line in the tang, this is somewhat unusual.

But Weapon 2 takes “setting the blade” to new levels: Not only is the actual grip 1/4″ longer than that of its mate, the handle actually curves down so far that the end of the pommel is flush with the rim of the bell guard. (That means the handle had to be custom-made from two pieces of wood hollowed out to take in the curved tang!) That guard has a diameter of 4″, meaning that the pommel deviates twice as much from the center as that of its mate!

This may reflect the mind of a fellow attorney at work: If the rules of engagement called for 34″ blades of equal length, they’re in full compliance. But if the rules said nothing about the permissible length and angulation of the handle, and if those differences were not necessarily obvious, then there was no reason not to take advantage of this!

Type 2, Weapon 2: Look at this set in the handle!

Modern épée fencers will of course immediately recognize the purpose of this setting: This configuration is ideal for “pommeling” or “posting”, i.e., gripping the weapon close to the pommel, thus adding two to three inches of offensive and defensive distance and a corresponding spectrum of possibly effective angulations to one’s game!

(This would place the origins of this tactic well into the mid-1800’s! We’ve earlier found evidence of it dating back to the 1920’s, right HERE.)

The amount of planning, customization, and deliberate design that went into assembling these two sets of dueling épées indicates that the upside-down mounting of blades—while providing no discernible advantage over the traditional configuration—was not a result of error or inept manufacture, but a matter of intent. At the same time, the weapons were designed for use, not mer representational purposes.

As such, we’re adding an additional category to our growing classification grid of dueling weapons—which we plan to publish here within the next couple of years!

Type A (below) vs. the standard mount.

Note: I attempted to discover any practical advantages of this combination by taking a concave-forward foil guard and an upside-down épée blade and trying it out against several fencers at a recent HEMA gathering at my club. I must report I did not detect any noticeable benefit! If you’ve made different observations, feel free to share!

Reblogged this on 50 Dueling Swords.

Hello,

as a collector I can only admit, that I also belong to those who believe(d) that these upside-down epees were the result of an unknowing wannabe weaponsmith. But they turn up way to often to be a mistake. Perhaps the concave part of the guard has a similar function as the rivettino on the Italian Masaniello Parise foils: to “catch” the tip of the blade and keep it from sliding past the guard. This would give far better protection against those accidental hits where the point scrapes over the guard to score a hit on the hand or forearm. Just an idea.

All the best

T.

Could the upside down blade shave been intended for left handers? When holding my smallsword replica used for hema (based around short epee blade) I often find myself holding it with the ridge of the blade up…am lefty.

No. Then the handles would be left-handed as well, and they clearly are not.

I was going to say pretty much what Volkel said. I am thinking about putting together a pair of duelling epees and need a source for centre-drilled bells. Any suggestions? Reply to mchlmcquown@gmail.com, please. Been too long since we’ve talked.

It seems to me, admittedly only as an astute observer, that a convex guard going away from the handle would allow for catching of trusts from the opponent. As opposed to a concave guard (from the thruster’s perspective), which would deflect a stab and allow for a recovery and subsequent stab, the convex guard allows for an almost catch of the stab and, therefore and advantage – the opportunity to catch and quickly thrust back. Again, this is only logical, visual, observation. I have no experience in the matter.